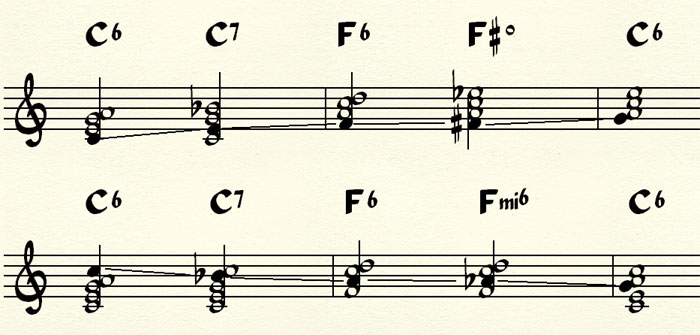

Rhythm: Three note chords - Why?

/Because of a comment on another post, I realized that I hadn't cover why the classic swing rhythm guitar voicings are three notes.

Consider the rhythm guitarist in a swing band: Allan Reuss in Goodman's Band, Freddie Green in Basie's, etc. It's you and your acoustic archtop versus 10 to 13 horns. You have to cut through and still provide the pulse. The answer is a three note chord.

While it might seem counter-intuitive that playing less notes will be heard better than more notes, but you have to think about being a knife. In a big band, the bass player, bass drum, the trombones and the left hand of the piano are below you, and the trumpets, saxes, cymbals, and the right hand of the piano are above you. In between all of these voices is a small notch - that's where the rhythm guitar goes. By filling that notch, and not trying to play any other notes, you're acting as knife, slicing through the mix.

If you play higher and lower notes, they'll just get lost in the mix of the other instruments. But the notes (especially on the D and G strings) can cut through the band. Think of that space as a hole in enemy lines - you need to get a small special forces squad through unnoticed, not try to cram a battalion through. Playing more notes in a big band just muddies things up. It blunts the rhythmic impact (which is really the primary thing), and it results in a lot of wasted effort.

Acoustic archtop guitars happen to have their natural peak in the mid-range on the D and G strings, between the 5th and 10th frets - basically prime rhythm guitar chord territory. By focusing on that region, you get the best return on your efforts.

When people talk about Freddie Green playing only or two note chords, he would basically be fingering the classic three note voices, but not fully pushing down the bass string, and/or or the G string. He would be focusing on the D and G strings for the maximum punch and cut.

I generally stick to the classic three note voicings for 90% of playing. Sometimes, in a bigger band, I'll drop the bass string. And sometimes, in a trio setting, I might add a fourth note, but I also might not. By focusing on only playing those three notes, it is also easier to check the rhythmic snap needed for the style.