New - Play-a-long Tracks

/While playing with other people is by far the best possible way to practice and improve, it can be hard to do all of your practice in public or at least with other people listening. Play-a-long tracks, whether in the Music-Minus-One or Jamey Abersold variety, are limited in their effectiveness because there is no give-and-take. Still, they can be helpful when woodshedding a new tune or trying to get your head around some changes.

But, the biggest problem with the current commercially available options, Abersold, etc. is the rhythm section playing. There is nothing even remotely resembling a pre-bebop swing rhythm section anywhere. Personally, I find it very difficult to achieve the sounds I'm going for in when playing along with a band that is rhythmically and harmonically incompatible.

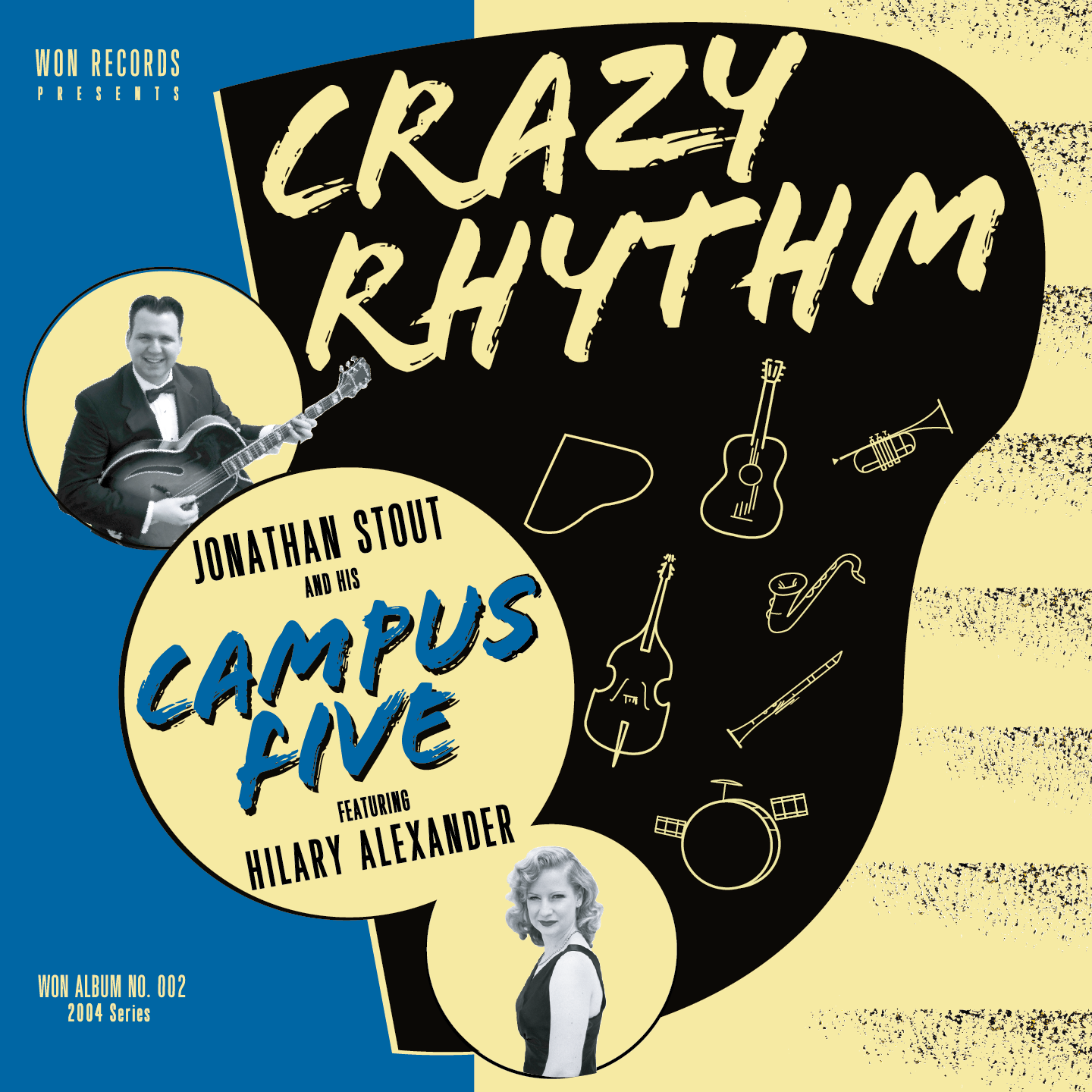

Eventually, I think I will probably record and release a proper album of play-a-long tracks with the Campus Five's rhythm section, but for now, how about some guitar-only rhythm tracks to practice with?

I've used the tracks at nuagesdeswing.free.fr for years, but I find the "Le Pompe" feel they have makes me play much more Django-y, and while I do enjoying playing that way, I have a hard time expressing more "american" ideas when playing over such a backing.

A word of advice on using play-a-long tracks, i find it helpful to play the melody of the song before diving into soloing over the changes. Often times the melody helps make sense of any interesting changes, and can lend insight to possible melodies and voice-leading, rather than mechanically running through the changes. I've provided three choruses on each track so you'll have space to play the melody before having two whole choruses to develop ideas over.

Here are four tunes: All of Me, Limehouse Blues, Rosetta, and Tea for Two:

All of me - playalong by campusfive

Limehouse Blues - playalong by campusfive

Rosetta - playalong by campusfive

Tea for Two - playalong by campusfive

And just for the heck of it, here are a couple takes of me playing over the tracks. FYI, all of these were recorded with my new Blue Yeti microphone - I specifically got it to facilitate recording stuff for the blog, examples, lessons, etc. The guitar is my Eastman AR805 with Martin SP 80/20 strings and a 2.5mm Wegen Pick.

All of me - playalong with lead by campusfive