Approaching Minor Keys, pt.1

/I've had many friends who have begun trying to play swing guitar after coming from a rock/pop background, not a modern jazz one. "Minor Swing" is a popular tune to start with, but many players without a jazz background can't figure out how to approach soloing over the chords.

Specifically, it's the minor pentatonic scale that is the backbone on much rock and blues that doesn't fit. The main culprit of this is the 7th scale degree (in Am, the G note) - it just doesn't fit over swing or early jazz minor songs. And there's good reason: the V7 chord.

Going back at least as far as Bach, classical music did not use the standard v chord of a mino key (key Am: A-B-C-D-E-F-G; a V chord based on this scale would be an E minor7: E-G-B-D). In classical music a V chord is always a DOMINANT 7 chord (in Am, an E7 chord: E-G#-B-D). There is pavlovian response to hearing the G# note it that chord, which demands that it be resolved to the A note.

With the G# note being so important, makes sense that the minor pentatonic scale doesn't fit with it's G natural note.

In classical and in early jazz and swing, they don't use the minor pentatonic scale, or the "natural" minor scale - which is just the normal notes of the key (in Am: A B C D E F G). Instead, they both use a minor scale with a raised 7th (in Am, a G# note). There are two minor scales that contain a raised 7th that are used extensively in early jazz and swing, the harmonic minor and the jazz minor.

The harmonic minor scale dates back to at least Bach, and has a particularly "European" sound (at least to my ears). It is a natural minor scale with a raised 7th (in Am: A B C D E F G#).

The jazz minor is comparatively younger, and has a more "American" sound (again to my ears). It is a natural minor scale with both a raised 7th, and a raised 6th (in Am: A B C D E F# G#).

By "American" and "European", I'm really getting at the distinction between the gypsy-influenced hot jazz of Django, and the less classical sounding playing of American swing musicians, like say, Charlie Christian. Charlie was more likely play more raised 6ths and feature them as an important note in his phrasing. Django was at least equally as likely to play either a regular or raised 6th, and perhaps more likely to play the regular 6th. American pre-bebop jazz harmony often voiced a minor i chord as a im6, which contains the raised 6th. But it should be noted that even if there is a raised 6th in the harmony, the soloist can also use the regular 6th, as Django did, even though it technically shouldn't fit.

In all harmony, some notes are "functional" in the sense that they are guide tones important to voice leading and chordal movement. Other notes are not, and there for they can be approached less strictly. The 7th scale degree is clearly a functional note, whereas the 6th scale degree is not. That's why you can often play either 6th with no problem, but that natural 7th just doesn't sound right.

Even modern jazzbos have a hard time approaching pre-bop minor key tunes. When Miles Davis released "Kind of Blue" in 1959, he ushered in a new era of modal jazz, specifically based on the Dorian mode, with "So What", being the chief example.

The Dorian mode is a natural minor scale with a raised 6th (like the jazz minor), but NOT the raised 7th (in Am: A B C D E F# G).. The sound of the Dorian mode is based on a minor7 chord as the tonic, and there for the regular 7th scale degree fits. Many modern jazzbos have forgotten the older-style sound of pre-bop, and just ignorantly play Dorian over everything. I avoid musicians like that like the plague.

As a early jazz/swing style musician, one should learn both the harmonic minor and jazz mimor scales like the back of one's hand. Part 2 will feature some musical examples.

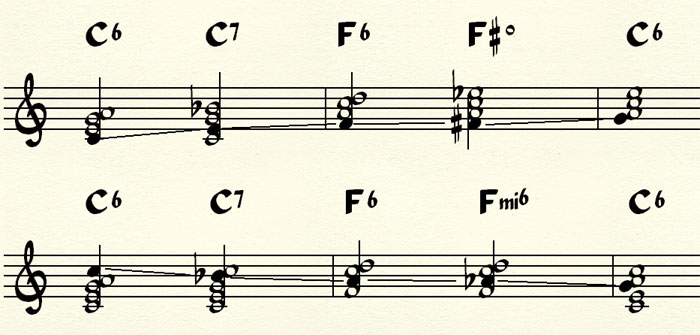

Here are the scales in question with the i and V chords built on those scales.